I spent some time on the Catholic Answers forums the other day. I have an interest in moral theology and so browsed through those forums, and was a little surprised by what I believe to be widespread confusion concerning the nature of sin. Take for example one of the most popular topics, masturbation. Over and over again the sin of masturbation was excused because of habitual or social factors. Masturbation was a sin, most maintained, but couldn't be a mortal sin because it was a habit, or the world presents too many temptations, or for some other reason.

The problem with all this moral hair-splitting and modern psychology is that the concept of sin is essentially eliminated.

What I mean is this: every outward action of a person has social or circumstantial elements because human beings are both social and contingent beings. A reasonable theology of sin must be able to incorporate this human reality without eliminated the very concept of sin. To say that an individual must have perfect voluntariness for something to be a mortal sin and to mean by this that there cannot be circumstantial or social contingencies in his outward act is the same as saying that a man cannot commit a mortal sin. Mortal sin is the preserve of Angels. I'm reminded that even the first sin had a social aspect and a temptor. Were Adam and Eve completely free, did their action represent perfect knowledge and perfect will? The very foundation of our religion demands that we be able to answer yes, and yet Eve was tempted and Adam tricked. I repeat, every action of a man has social and circumstantial components.

We can perhaps get around this if we simply bury the sin a little deeper in the man and say that whatever component of the decision which was completely free and in no way contingent on external circumstances or influences, no matter how tiny, is were sin resides. In doing this we can allow for any amount of circumstantial or social influence without eliminating sin. However, the sin of the person becomes far removed from the external action. As long as we maintain that there exists even an infinitely small amount of freedom of the individual from society and from his own psychosis, even if it is so small that it is incapable of influencing his actual external actions, there is room for sin. The point, however, is that the more we build up psychological analysis and “social construction of reality” theories, the deeper we push the concept of sin into the mysterious core of the individual.

In principle this is fine, but if we are going to think about sin this way we have to reevaluate what we mean by grave matter. The definitions that we inherit from tradition are based on a concept of the will that was much more free than modern psychology maintains. Traditionally the social and circumstantial elements in an individual’s actions where simply taken for granted. Masturbation was a grave sin not because someone had perfect freedom from social pressures; rather it was grave matter assuming the scandalous influence of the world. So, if we are going to isolate sin from society we need to isolate grave matter from society. It would no longer be coherent to talk about grave matter that involves other people or their influences. Masturbation itself ceases to be sinful matter. However, all we are really doing is shifting the sinful action into that tiny corner of the individual’s psyche that is free from influence. And so, the rebellion to lust that necessarily occurs, no matter how deep in the individual’s soul, every time he masturbates is the grave matter.

The point is we can’t have it both ways. We can’t psychoanalysis ourselves virtually out of existence and then retain the lists of grave matter from the Middle Ages. The list of grave matter sins needs to keep pace, or we need to just accept the fact that we sin because we like it and that we know that it is wrong and that we do it anyway and that this is mortal sin!

In his Confessions, St. Augustine writes of his time among the Manichean heretics:

"For it still seemed to me “that it is not we who sin, but some other nature sinned in us.” And it gratified my pride to be beyond blame, and when I did anything wrong not to have to confess that I had done wrong--“that thou mightest heal my soul because it had sinned against thee” --and I loved to excuse my soul and to accuse something else inside me (I knew not what) but which was not I. But, assuredly, it was I, and it was my impiety that had divided me against myself. That sin then was all the more incurable because I did not deem myself a sinner. It was an execrable iniquity, O God Omnipotent, that I would have preferred to have thee defeated in me, to my destruction, than to be defeated by thee to my salvation. Not yet, therefore, hadst thou set a watch upon my mouth and a door around my lips that my heart might not incline to evil speech, to make excuse for sin with men that work iniquity. And, therefore, I continued still in the company of their “elect.”"

Monday, July 16, 2007

Tuesday, May 1, 2007

Food for thought

"That the State must be separated from the Church is a thesis absolutely false, a most pernicious error. Based, as it is, on the principle that the State must not recognize any religious cult, it is in the first place guilty of a great injustice to God; for the Creator of man is also the Founder of human societies, and preserves their existence as He preserves our own. We owe Him, therefore, not only a private cult, but a public and social worship to honor Him. Besides, this thesis is an obvious negation of the supernatural order. It limits the action of the State to the pursuit of public prosperity during this life only, which is but the proximate object of political societies; and it occupies itself in no fashion (on the plea that this is foreign to it) with their ultimate object which is man's eternal happiness after this short life shall have run its course. But as the present order of things is temporary and subordinated to the conquest of man's supreme and absolute welfare, it follows that the civil power must not only place no obstacle in the way of this conquest, but must aid us in effecting it. The same thesis also upsets the order providentially established by God in the world, which demands a harmonious agreement between the two societies. Both of them, the civil and the religious society, although each exercises in its own sphere its authority over them. It follows necessarily that there are many things belonging to them in common in which both societies must have relations with one another. Remove the agreement between Church and State, and the result will be that from these common matters will spring the seeds of disputes which will become acute on both sides; it will become more difficult to see where the truth lies, and great confusion is certain to arise. Finally, this thesis inflicts great injury on society itself, for it cannot either prosper or last long when due place is not left for religion, which is the supreme rule and the sovereign mistress in all questions touching the rights and the duties of men. Hence the Roman Pontiffs have never ceased, as circumstances required, to refute and condemn the doctrine of the separation of Church and State. Our illustrious predecessor, Leo XIII, especially, has frequently and magnificently expounded Catholic teaching on the relations which should subsist between the two societies. "Between them," he says, "there must necessarily be a suitable union, which may not improperly be compared with that existing between body and soul. - Quaedam intercedat necesse est ordinata colligatio (inter illas) quae quidem conjunctioni non immerito comparatur, per quam anima et corpus in homine copulantur."He proceeds: "Human societies cannot, without becoming criminal, act as if God did not exist or refuse to concern themselves with religion, as though it were something foreign to them, or of no purpose to them.... As for the Church, which has God Himself for its author, to exclude her from the active life of the nation, from the laws, the education of the young, the family, is to commit a great and pernicious error. - Civitates non possunt, citra scellus, gerere se tamquam si Deus omnino non esset, aut curam religionis velut alienam nihilque profuturam abjicere.... Ecclesiam vero, quam Deus ipse constituit, ab actione vitae excludere, a legibus, ab institutione adolescentium, a societate domestica, magnus et perniciousus est error." Pope Pius X, VEHEMENTER NOS

Thursday, April 12, 2007

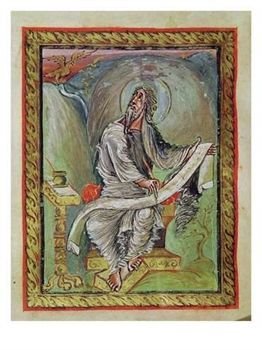

Again inspired by a post on the Ignatius Press blog concerning church architecture, I offer a few thoughts:

The dearth of good church architecture should be understood as an aspect of the general decline of all religious art. Art, as artists constantly remind us, is a language by which the artist non-verbally expresses his very being. True religious art can, therefore, only be produced by a deeply religious, praying soul. Such art inspires those who share the artist’s spiritual disposition at a visceral, non-verbal level. When we talk about art, when we analyze it and critique it, we are attempting to translate from the language of art to language proper, and like all translations something is invariably lost.

The process is generally backward today. A secular architect, hired by a parish, is not expressing his very soul, unmediated by language. Rather, the faithful try to translate their spiritual life into language, tell him about it, and then he tries to translate it into art. Such third-hand art cannot possibly inspire. It will always be cold, banal, and predictable.

No less banal, though aesthetically worthy of far more respect, are attempts at mimicking the architecture of the past. In order to have inspirational Christian architecture, we must have inspired Christian architects.

The dearth of good church architecture should be understood as an aspect of the general decline of all religious art. Art, as artists constantly remind us, is a language by which the artist non-verbally expresses his very being. True religious art can, therefore, only be produced by a deeply religious, praying soul. Such art inspires those who share the artist’s spiritual disposition at a visceral, non-verbal level. When we talk about art, when we analyze it and critique it, we are attempting to translate from the language of art to language proper, and like all translations something is invariably lost.

The process is generally backward today. A secular architect, hired by a parish, is not expressing his very soul, unmediated by language. Rather, the faithful try to translate their spiritual life into language, tell him about it, and then he tries to translate it into art. Such third-hand art cannot possibly inspire. It will always be cold, banal, and predictable.

No less banal, though aesthetically worthy of far more respect, are attempts at mimicking the architecture of the past. In order to have inspirational Christian architecture, we must have inspired Christian architects.

Tuesday, March 20, 2007

There is a post on the Ignatius Press Blog this morning that I found confusing. Essentially they were discussing what to call protestants. The consensus seemed to be that it was appropriate to call them "fellow believers."

I converted from atheism and nihilism, and my conversion was very philosophical. I became convinced that either the divine Logos, the very principle of truth, existed and had descended and become one of us, and that this communication of the divine reason continued unabated, or we had no way to get out of our own heads.

My thinking went something like this: All the universe is a thought. Either our own, as the post-modernists would have it, or God's. If it's our own than there is no truth, there is no way out of the thought. If it is God's there is still no way to know what is true and what isn't unless God's thought and the world we perceive are one and the same. But we have no way of knowing this unless God affirms it. This happened in Christ. But if it was a one-time event, if the divine Logos descended and then re-ascended, we are again left in the same predicament: how can we know who Christ was, how can we know what parts of the universe as we perceive it are affirmed and what parts denied? If the incarnation was the whole story, are not we in the same epistemological fog as the generations before the incarnation?

My conclusion was that either the thought of God continued to directly affirm the existence of the world and of us as individuals in it or we could know nothing. But how could the affirmation of God touching the world be communicated to us without the problem of our own minds popping up again. How could the truth be communicated to us in a way that it defeated the sceptical argument? My answer was that the communication could not be verbal or symbolic or in anyway limited; it had to be total and to the entire person, it had to transcend the labels and categories of language and thought: in short there had to be a soul and grace that touched it, but this grace had to be communicated to us in a manner that reaffirmed the existence of the universe and our existence as distinct persons in it. I became convinced that the incarnation of the Divine Logos either bestows grace on us perpetually through the sacraments of the Catholic Church or the only philosophically consistent option was nihilism. I realize this may sound convoluted and unconvincing, and actually as I reconsider it I find much less necessary than I once had, and I have since learned to love and to pray and have developed a faith that views my previous ideas as somewhat adolescent. But nevertheless, to me Christianity continues to be, in its essence, a sacrament.

And so the assertion that protestants are fellow believers in confusing to me. It seems to me that protestantism most certainly denies “central mysteries” of the faith, namely the sacraments. The denial that the incarnational mission of Christ continues directly through the sacraments is no small departure or fine theological point. In his commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, St. Thomas went so far as to assert that the establishment of the Eucharist and the priesthood that confects it was the reason for Christ's incarnation. To deny that God continues to touch man directly and materially and in a manner no way diminished from when he actually walked and died among us, in favor of a religion that understands man's relationship with God as being purely spiritual is, it seems to me, to revert to Judaism. The sacraments are not Catholic “bonuses” that are tacked on to the essentials of Christian faith and “separated” believers are rightly considered protestant to the extent that they deny the essential, sacramental nature of Christianity. This would suggest that the more protestant one is, the less Christian. But I’m no theologian; maybe I’m wrong. If so, could someone please explain to me my error.

I converted from atheism and nihilism, and my conversion was very philosophical. I became convinced that either the divine Logos, the very principle of truth, existed and had descended and become one of us, and that this communication of the divine reason continued unabated, or we had no way to get out of our own heads.

My thinking went something like this: All the universe is a thought. Either our own, as the post-modernists would have it, or God's. If it's our own than there is no truth, there is no way out of the thought. If it is God's there is still no way to know what is true and what isn't unless God's thought and the world we perceive are one and the same. But we have no way of knowing this unless God affirms it. This happened in Christ. But if it was a one-time event, if the divine Logos descended and then re-ascended, we are again left in the same predicament: how can we know who Christ was, how can we know what parts of the universe as we perceive it are affirmed and what parts denied? If the incarnation was the whole story, are not we in the same epistemological fog as the generations before the incarnation?

My conclusion was that either the thought of God continued to directly affirm the existence of the world and of us as individuals in it or we could know nothing. But how could the affirmation of God touching the world be communicated to us without the problem of our own minds popping up again. How could the truth be communicated to us in a way that it defeated the sceptical argument? My answer was that the communication could not be verbal or symbolic or in anyway limited; it had to be total and to the entire person, it had to transcend the labels and categories of language and thought: in short there had to be a soul and grace that touched it, but this grace had to be communicated to us in a manner that reaffirmed the existence of the universe and our existence as distinct persons in it. I became convinced that the incarnation of the Divine Logos either bestows grace on us perpetually through the sacraments of the Catholic Church or the only philosophically consistent option was nihilism. I realize this may sound convoluted and unconvincing, and actually as I reconsider it I find much less necessary than I once had, and I have since learned to love and to pray and have developed a faith that views my previous ideas as somewhat adolescent. But nevertheless, to me Christianity continues to be, in its essence, a sacrament.

And so the assertion that protestants are fellow believers in confusing to me. It seems to me that protestantism most certainly denies “central mysteries” of the faith, namely the sacraments. The denial that the incarnational mission of Christ continues directly through the sacraments is no small departure or fine theological point. In his commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, St. Thomas went so far as to assert that the establishment of the Eucharist and the priesthood that confects it was the reason for Christ's incarnation. To deny that God continues to touch man directly and materially and in a manner no way diminished from when he actually walked and died among us, in favor of a religion that understands man's relationship with God as being purely spiritual is, it seems to me, to revert to Judaism. The sacraments are not Catholic “bonuses” that are tacked on to the essentials of Christian faith and “separated” believers are rightly considered protestant to the extent that they deny the essential, sacramental nature of Christianity. This would suggest that the more protestant one is, the less Christian. But I’m no theologian; maybe I’m wrong. If so, could someone please explain to me my error.

Tuesday, March 13, 2007

When I was reflecting on the upcoming presidential election, and the pleading of many Republicans that conservatives and Christians be “reasonable,” I was reminded of something that Henri De Lubac, S.J., one of twentieth century’s greatest theologians, wrote:

"…He is not an extremist, nor a biased man. He is a wise man, fair. He is wary of all passion. Moreover, he has experience, he knows that in all matters there is wrong on both sides and that nothing is to be gained by looking too closely. He knows too that you have to live and that life is impossible without mutual concessions and a certain ‘happy medium.’ In all controversies he suffers at seeing two men ‘attacking one another.’ It is also one of his maxims that there is always a risk in running foul of any accepted opinion whatever. Therefore people often have recourse to his arbitration. Of two adversaries who take him to witness, if one says that two and two make five, and the other that they make four, he prudently inclines toward the middle solution: two and two, he suggests, more or less make four and a half." Henri De Lubac, S.J.

"…He is not an extremist, nor a biased man. He is a wise man, fair. He is wary of all passion. Moreover, he has experience, he knows that in all matters there is wrong on both sides and that nothing is to be gained by looking too closely. He knows too that you have to live and that life is impossible without mutual concessions and a certain ‘happy medium.’ In all controversies he suffers at seeing two men ‘attacking one another.’ It is also one of his maxims that there is always a risk in running foul of any accepted opinion whatever. Therefore people often have recourse to his arbitration. Of two adversaries who take him to witness, if one says that two and two make five, and the other that they make four, he prudently inclines toward the middle solution: two and two, he suggests, more or less make four and a half." Henri De Lubac, S.J.

I am afraid that conservative Catholics have made some of the very same mistakes concerning American politics as did the liberals in the sixties and seventies. During the 60s and 70s, in their desire for peace and justice, many faithful Catholics, including the greater part of the episcopate, aligned themselves with the political left. The political left seemed to be allied with the Catholic Church in matters economic and political. In their alignment with the political the left, these Catholics allowed partisanship and loyalty to their “friends” to blind them to the fact that the philosophy of the left is diametrically opposed to the truths of Christianity—now the left has definitively shown it’s true colors: it hates Christianity and Christians. The Christian allies of the left have in recent years either stopped being Christian or drifted away from the left-- Just look what has happened with the bishops. Peace and Justice Christians who are serious about their Christianity are only now beginning to realize what a terrible mistake they made when they threw in with the progressive crowd—but it’s too late. The damage has been done. The Church is on the verge of demographic collapse and general persecution. I’m afraid the conservatives in the Church are making the same mistake with the political right. Free-market capitalism, majority-rule government, the spread of Enlightenment ideology—these things are not Catholic. It pains me to see Catholics embracing American nationalism, and talking about protecting “American culture” as if the pornography, moral relativism, individualism, and greed that our culture mass produces and exports all over the world are things worth defending. We can already see that the so-called neo-cons are annoyed with the religious hang-ups of their allies in the Church. The conservatives in the Church who think they have made a home in the Republican Party are going to be in for a surprise similar to that the liberal Catholics in the Democratic Party have experienced, when their children, raised to defend American bigotry, capitalism, and war, decide that the Catholic Church is not where they belong. They will either leave the Church and become non-denominational individualists, or they will become secular Wall-Street conservatives, or neo-con hawks.

We need to hunker down, regroup, learn from our mistakes, and start to re-evangelize. We need to realize that the world, has rejected Christ, and the world will reject us. We can have no home in American politics.

We need to hunker down, regroup, learn from our mistakes, and start to re-evangelize. We need to realize that the world, has rejected Christ, and the world will reject us. We can have no home in American politics.

Friday, February 23, 2007

There has been a lot of talk recently about Pope Benedict XVI and the universal indult. Now, I've heard talk of some sort of juridical structure specifically for the priests who elect to say the Roman Mass, so they will be free from reprisals for doing so. I have never experienced the Old Roman Rite, but I feel a deep spiritual desire to be united with centuries of Christian worship. For this reason I look forward to the possibility that the traditional liturgy will become more available. I have some reservations, however. I worry that we are heading toward two distinct institutions: the "high" (Latin, Old Rite) Catholic Church and the "low" (vernacular, Novus Ordo) Catholic Church. We can see in the Anglican Church this exact phenomenon. This danger seems to be increased by the prospects of a juridical structure outside of regular diocesan structure. Are we headed to a virtual split in the Latin Rite Church akin to the split that exists today between the Latin and Byzantine Rites? If the "high" Catholics leave the "low" Catholic parishes and flee to the Old Rite, what will become of the rank-and-file Churchgoer? Who will moderate the more radical of the liberals in our parishes?

I'm afraid ever since great variations arose between parishes this phenomenon has been growing. Already the idea of the parish as a geographical entity is fading in favor of it as a purely elective community. This mirrors the general replacement of communities with cliques throughout society, and the concurrent increase in mobility, the demise of the extended family, and all that fun stuff. We have to ask ourselves, is allowing the separation of the conservatives from the mainstream (liberal) Catholics another example of the Church caving to the culture of extreme individualism?

Rather, I hope that we could have a situation where one of a parish's many Sunday Masses would be the old Rite. Or, better yet, if there is a true acknowledgement that something great has been lost, we can slowly, organically reintroduce those components into the new canon. It was over intellectualization, and a lack of respect for the power of culture and history, that convinced us that it was okay to "design" our liturgies in the first place. Is it not the case that the liturgy must flow from the action of worship itself, that only when the people are living as Christians will a truly Christian liturgy emerge? If our parishes were full of devote Christians, our liturgies would become a true expression of that devotion. We might be surprised how, if a renewal of faith in the hearts of the Catholic population occurred, the new canon and old might merge, that the distinction between the two would become purely academic, because regardless of which book the priest was reading from, the people would be united in adoration, in prayer, and in Sacrament with the Church past, present, and future.

As people we necessarily live in culture. The inner spirit of the culture is expressed in every action of the people: philosophy, theology, prayer, art, music, politics, family, etc. We must believe in our hearts, to our very core, to the point were our every action is an expression of our membership in the Church of Christ. This expression cannot be translated into intellectual formulations, into mere words; to do this is to raise the intellectual aspect of culture above the rest. It is this error that has led us to believe that as long as the books on the shelves still profess the doctrinal formulations of the Church that we are still Catholic-- this is a mistake. I pray that we are not making the same mistake in advocating the re-introduction of the Old Rite. Let us remember, the vast majority of us have never seen it.

All in all, though, I have to support the return of the Old Rite. But, I fear my reason for this support is persistent hopelessness. Let us pray for Hope.

I'm afraid ever since great variations arose between parishes this phenomenon has been growing. Already the idea of the parish as a geographical entity is fading in favor of it as a purely elective community. This mirrors the general replacement of communities with cliques throughout society, and the concurrent increase in mobility, the demise of the extended family, and all that fun stuff. We have to ask ourselves, is allowing the separation of the conservatives from the mainstream (liberal) Catholics another example of the Church caving to the culture of extreme individualism?

Rather, I hope that we could have a situation where one of a parish's many Sunday Masses would be the old Rite. Or, better yet, if there is a true acknowledgement that something great has been lost, we can slowly, organically reintroduce those components into the new canon. It was over intellectualization, and a lack of respect for the power of culture and history, that convinced us that it was okay to "design" our liturgies in the first place. Is it not the case that the liturgy must flow from the action of worship itself, that only when the people are living as Christians will a truly Christian liturgy emerge? If our parishes were full of devote Christians, our liturgies would become a true expression of that devotion. We might be surprised how, if a renewal of faith in the hearts of the Catholic population occurred, the new canon and old might merge, that the distinction between the two would become purely academic, because regardless of which book the priest was reading from, the people would be united in adoration, in prayer, and in Sacrament with the Church past, present, and future.

As people we necessarily live in culture. The inner spirit of the culture is expressed in every action of the people: philosophy, theology, prayer, art, music, politics, family, etc. We must believe in our hearts, to our very core, to the point were our every action is an expression of our membership in the Church of Christ. This expression cannot be translated into intellectual formulations, into mere words; to do this is to raise the intellectual aspect of culture above the rest. It is this error that has led us to believe that as long as the books on the shelves still profess the doctrinal formulations of the Church that we are still Catholic-- this is a mistake. I pray that we are not making the same mistake in advocating the re-introduction of the Old Rite. Let us remember, the vast majority of us have never seen it.

All in all, though, I have to support the return of the Old Rite. But, I fear my reason for this support is persistent hopelessness. Let us pray for Hope.

Thursday, February 22, 2007

Friday, February 16, 2007

It seems to me that the feminist gender theory conviction that gender roles are socially constructed and their conclusion that, therefore, they are artificial and infinitely malleable is seriously flawed. First of all, anyone who believes that men and women do not have genetic differences in their personalities and dispositions is a fool.

I can normally see where people are coming from in their beliefs. I can understand why someone might be a Marxist or even an anarchist; I can understand why someone would be an Atheist. I do not believe people who hold these convictions are necessarily fools. But people who believe there are no innate differences between men and women are fools. Of course there is.

That said, however, my primary objection with the gender role people is not along those lines. In fact, I believe that a great deal of what we understand as the dominant differences between men and women probably are, at least partially, socially constructed. Where I really disagree with them is their equating the socially constructed with the artificial-- With their idea that the socially constructed is a non-essential aspect of humanity.

Mother lions have to teach their cubs how to hunt. It in no way follows that hunting is an artificial and non-essential aspect of what it means to be a lion. In fact, we all recognize that a lion that is born in captivity, or an orphan cub, who never learns to hunt has been robbed of something of what it means to be a lion, and we are right. They are “almost” lions. This is the case because lions are social animals and being a social animal means more than being an animal that happens to share a meal or a den. Social animals require each other. They are not complete without society. A lion, unlike an insect, is not defined completely by their genome, something intrinsic to being a lion resides outside of any given individual, and they share it.

Humans are, of course, far more sophisticated than lions, and far more social. As Aristotle noted a man who lives outside of society is a god or an animal, not a man. This does not mean that we just happen to like each other, or that somewhere along the line, as Locke and Hobbes entertained, a bunch of independent humans came together because it was more profitable. Rather, it means that the very structure of what it means to be a human includes a community. Modern thought, especially linguistics, never tires of driving home the point that culture is an intrinsic component of humanity and not something tacked on, something that can be discarded. Mankind has far less instinct and far more culture than any other animal.

So the assumption that the cultural component of gender roles is necessarily unnatural or imposed is unfounded. Now they would argue that it is at least subject to change, that it is exactly the ability of culture to change that allows for remarkable adaptability of man, and they would be right. It can change. But then the question becomes not whether people reinforce gender roles when they give their daughters dolls and their sons guns, the question is whether these gender roles are like hunting for a lion—whether they are something we can do without, or when we rob a little girl or boy of their culturally conditioned femininity or masculinity they are like the orphan lion cub— sad specimens of “almost” humans. Only in that case what they are expected to live without is the very framework by which we understand social interaction at the most basic level, that of procreation.

Now I think that gender roles are precisely such essential culturally constructed aspects of humanity that work in conjunction with biological facts to create stable, healthy, and happy societies. That I am mistaken in this belief is what feminists have to convince me. Good Luck.

I can normally see where people are coming from in their beliefs. I can understand why someone might be a Marxist or even an anarchist; I can understand why someone would be an Atheist. I do not believe people who hold these convictions are necessarily fools. But people who believe there are no innate differences between men and women are fools. Of course there is.

That said, however, my primary objection with the gender role people is not along those lines. In fact, I believe that a great deal of what we understand as the dominant differences between men and women probably are, at least partially, socially constructed. Where I really disagree with them is their equating the socially constructed with the artificial-- With their idea that the socially constructed is a non-essential aspect of humanity.

Mother lions have to teach their cubs how to hunt. It in no way follows that hunting is an artificial and non-essential aspect of what it means to be a lion. In fact, we all recognize that a lion that is born in captivity, or an orphan cub, who never learns to hunt has been robbed of something of what it means to be a lion, and we are right. They are “almost” lions. This is the case because lions are social animals and being a social animal means more than being an animal that happens to share a meal or a den. Social animals require each other. They are not complete without society. A lion, unlike an insect, is not defined completely by their genome, something intrinsic to being a lion resides outside of any given individual, and they share it.

Humans are, of course, far more sophisticated than lions, and far more social. As Aristotle noted a man who lives outside of society is a god or an animal, not a man. This does not mean that we just happen to like each other, or that somewhere along the line, as Locke and Hobbes entertained, a bunch of independent humans came together because it was more profitable. Rather, it means that the very structure of what it means to be a human includes a community. Modern thought, especially linguistics, never tires of driving home the point that culture is an intrinsic component of humanity and not something tacked on, something that can be discarded. Mankind has far less instinct and far more culture than any other animal.

So the assumption that the cultural component of gender roles is necessarily unnatural or imposed is unfounded. Now they would argue that it is at least subject to change, that it is exactly the ability of culture to change that allows for remarkable adaptability of man, and they would be right. It can change. But then the question becomes not whether people reinforce gender roles when they give their daughters dolls and their sons guns, the question is whether these gender roles are like hunting for a lion—whether they are something we can do without, or when we rob a little girl or boy of their culturally conditioned femininity or masculinity they are like the orphan lion cub— sad specimens of “almost” humans. Only in that case what they are expected to live without is the very framework by which we understand social interaction at the most basic level, that of procreation.

Now I think that gender roles are precisely such essential culturally constructed aspects of humanity that work in conjunction with biological facts to create stable, healthy, and happy societies. That I am mistaken in this belief is what feminists have to convince me. Good Luck.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)